The anthropocene is a term that describes the current geological era. This term describes a period in which humanity is the leading force in geologically shaping the planet earth. While some scientists argue that this era began with organized agriculture in the 16th century, there are different views on its beginning, some associate it with the industrial revolution in the 19th century, or some argue that this era began in the 20th century in parallel with nuclear history. Regardless of the beginning of this period, today, climate change, which is one of the most catastrophic consequences of the present anthropocene era, is the top priority of the global agenda.

11 young designers who were in the Design Practicum class at Mason Gross School of the Arts, Rutgers University, in the state of New Jersey lead by design professor Atif Akin, approached this historical concept from different point of views and all visualized quantitative or encyclopedic data to create poetic meaning in the context of short animations. From microplastics to chicken bones, from political protocols to microscopic imaging techniques, from plastic bags to melting glaciers, they designed animations ranging from 30 to 60 seconds each. These animations are displayed at a whale size 39 feet LED screen at the Zorlu Performance Center in Istanbul

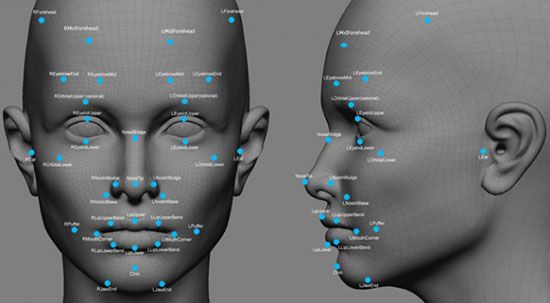

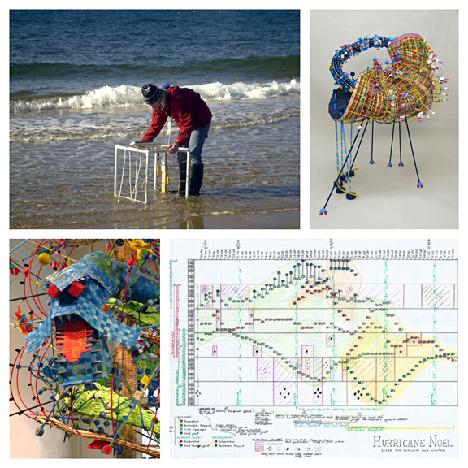

Katie Makar visualizes the sound recordings of the melting glaciers in the form of a wave and also points out the relationship between the melting glaciers and the rising sea level. Conor Finn deals with the aesthetics of the crisis screens of computer operating systems, adapting it to an animation that criticizes the environmental stalemate of the planet and its policies. Although it does not seem to have a very important place in the seriousness of the subject, 60 billion chickens produced and consumed each year and their bones are important in anthropocene research in the academic field. Taking this into account, Maya Tillman visualizes this striking data in fast food aesthetics. Francesca Stoppa, on the other hand, draws attention to the particle density in the atmosphere by acting with the data published by NASA in 2019. Animations there is also a small Turkish surprise inside, in limiting the use of plastic bags in Turkey, the United States a lot of the state from the early measures taken has learned that Sara Reed slightest a Turkish proverb, using the iconic New York plastic bag design. Tyler Lee not only experimented with electromicroscopic images that imply the technological advancement of humanity in. Poetic way, he also designed and implemented the visual identity of the project on behalf of his classmates. Elyssa Feerrar changes our point of view from the surface to the deep ocean and she created a cartoony looking dystopic underwater ocean view. While Jennifer Aguirre points our attention to urban deforestation, she uses images from both New York and Istanbul high rises. Both Lau Krystal and Jillian Mulhern were so much interested in the risk of microplastic pollution in the oceans, they took different ways of visualizing the phenomenon, while Jillian was interested in the consumer products Lau chose to literally and visually represent the microparticles on this whale size screen. Rushika Raman visualized number of chemical substances used in the plastic industry and their IUPAC names in a typographic animation that all started with “Poly-“.

For this international collaboration, organized by Deniz Akgüllü, director of digilogue sponsored by Zorlu Holding, we found this concept worth considering and scrutinizing as it is an issue of equal concern to everyone on the planet, from Istanbul to New Brunswick, New Jersey.

You can also view and download the whole animation in its original format: