Reception: Feb 12, 6–9 pm

On view: Feb 12 – Feb 28

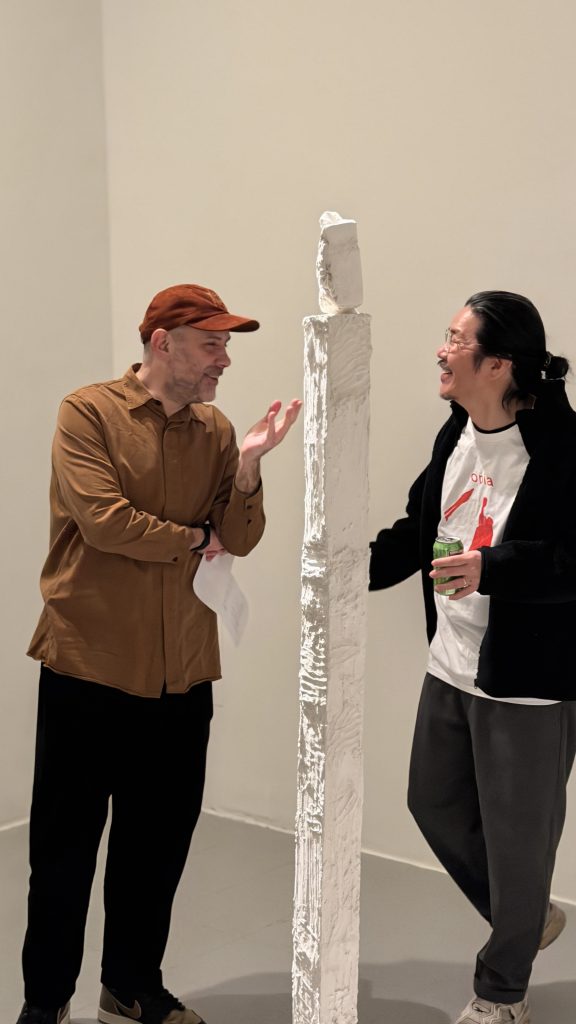

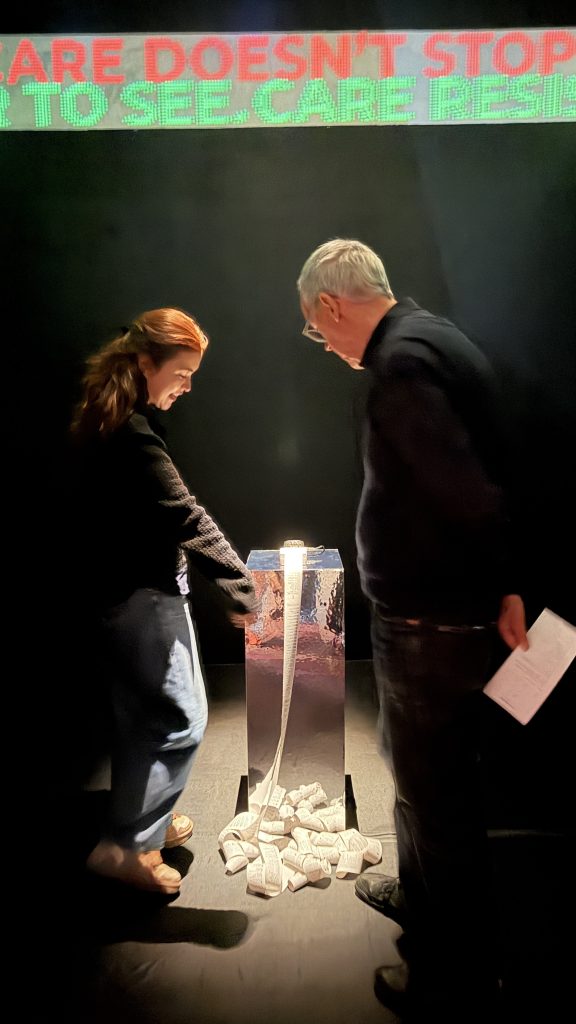

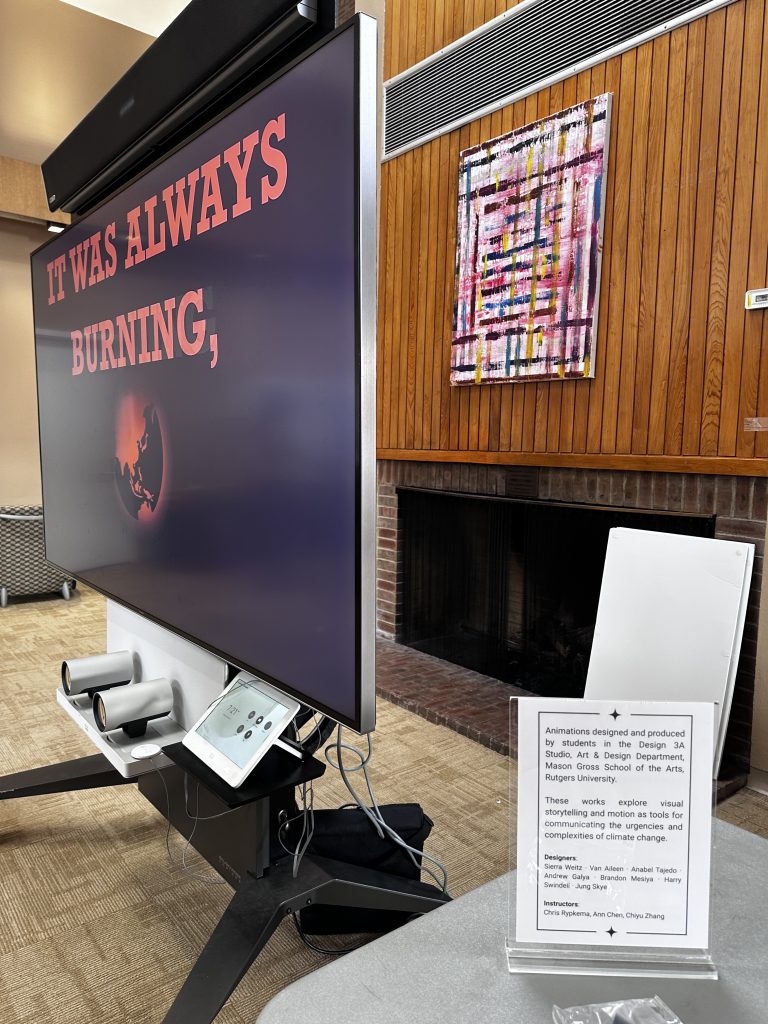

The second part of A Simultaneity Mark opened with a packed and animated reception, bringing together faculty, students, and visitors from across the Mason Gross community. The galleries carried a steady flow of conversations, with design and visual art audiences naturally overlapping throughout the evening. The event felt lively, social, and deeply engaged.

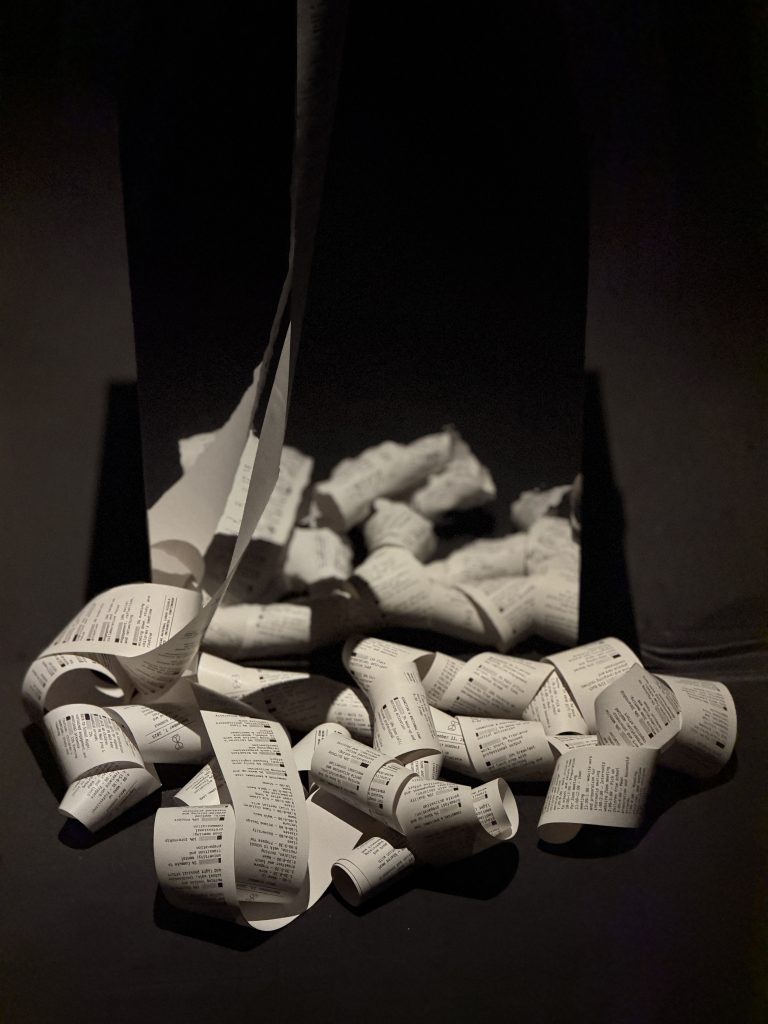

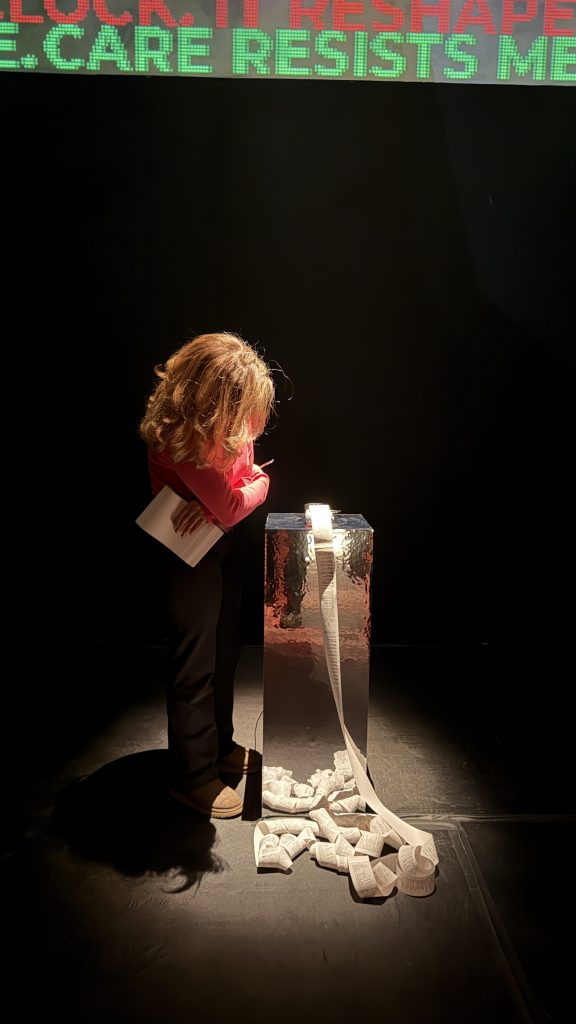

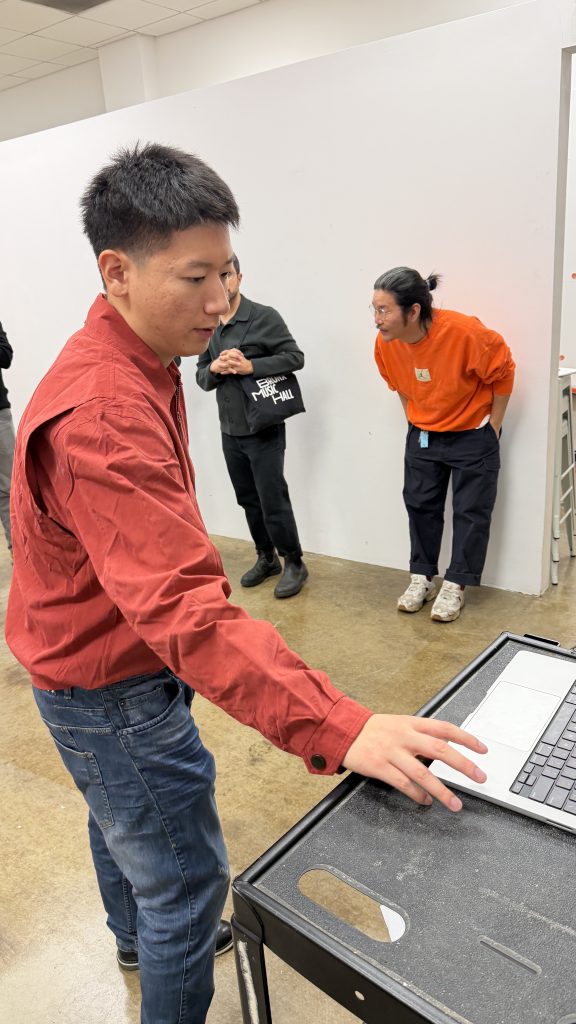

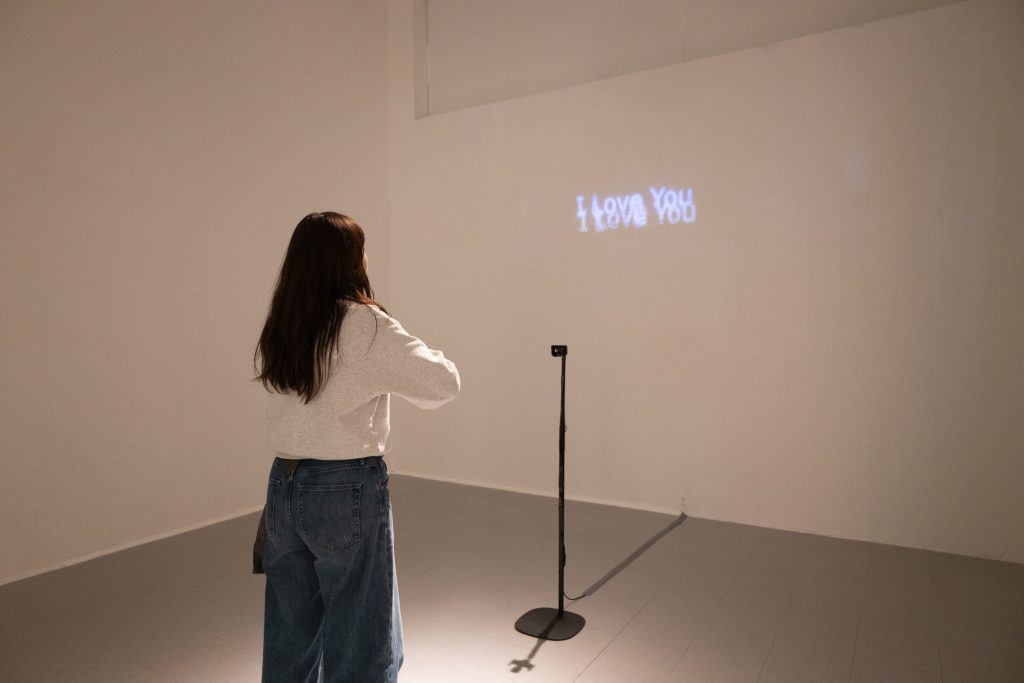

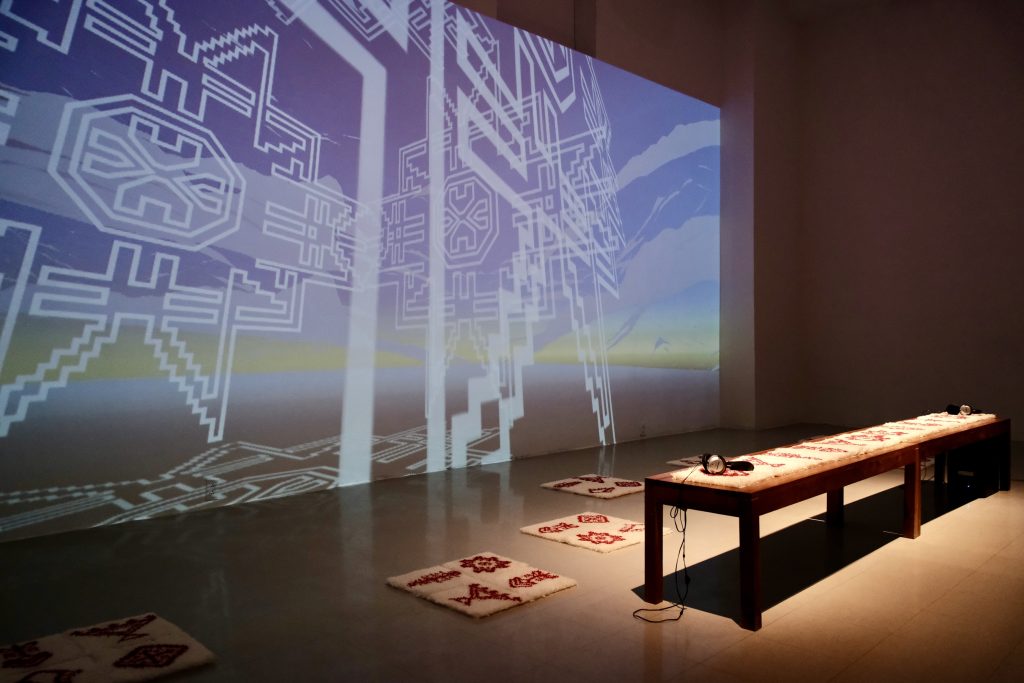

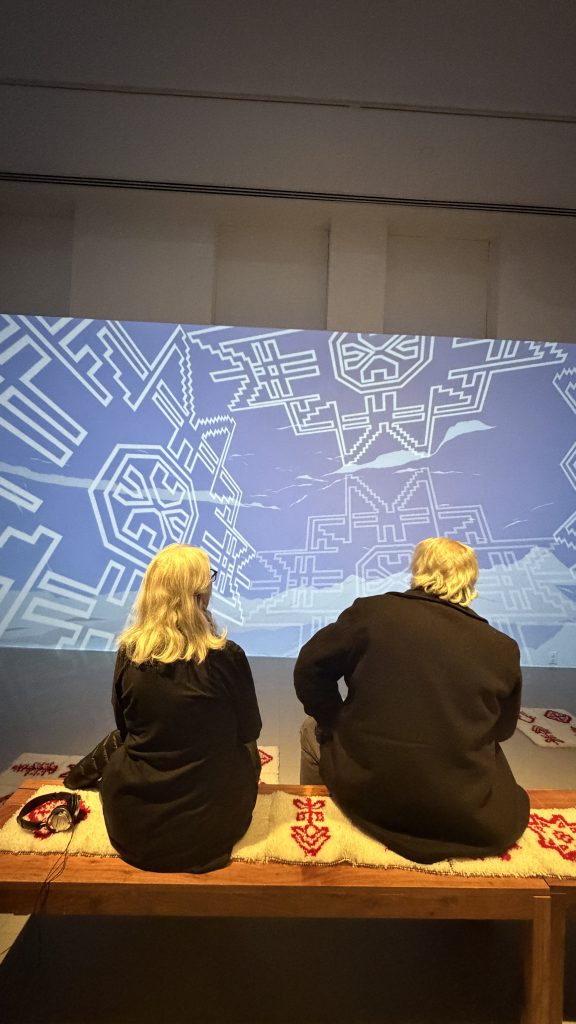

Each room constructed a different mode of experience. Chiyu Zheng’s interactive installation Gestic transformed subtle human hand movements into responsive texts, encouraging viewers to become aware of their own gestures and presence. Sabre introduced a shift in tempo, where Mahsa Masoumi’s work centered on duration, narrative, and repetition, drawing visitors into a slower, more reflective encounter shaped by image, sound, and pattern. Yuxuan Hu’s installations explored language perception and memory through generative imagery, producing visuals that appeared and dissolved in response to sound.

Beyond the design spaces, surrounding rooms of the gallery presented visual art works, creating a broader exhibition context and reinforcing the interdisciplinary atmosphere of the night. The exhibition remained open to the public through February 28, extending the reception’s energy into an ongoing viewing experience.

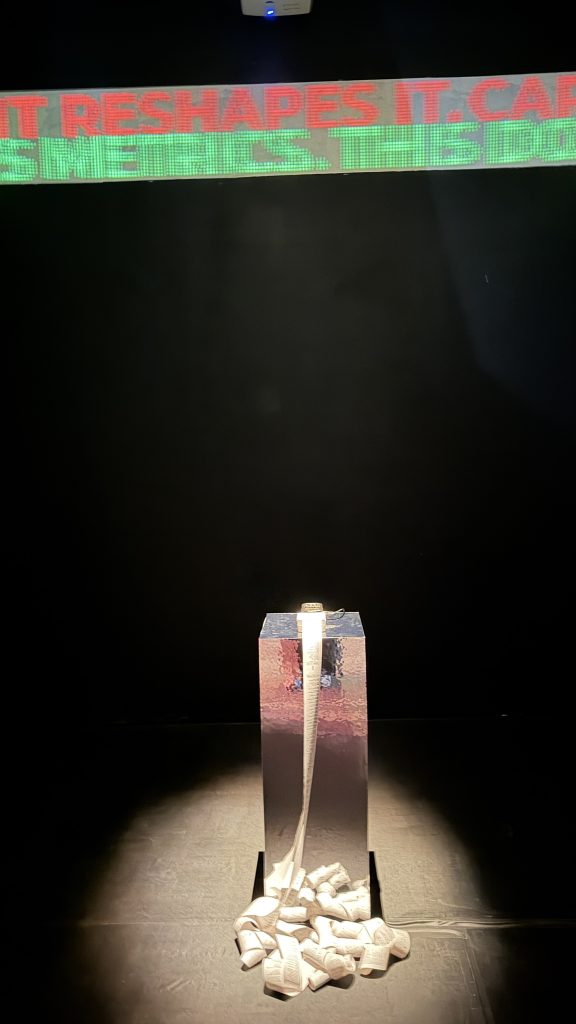

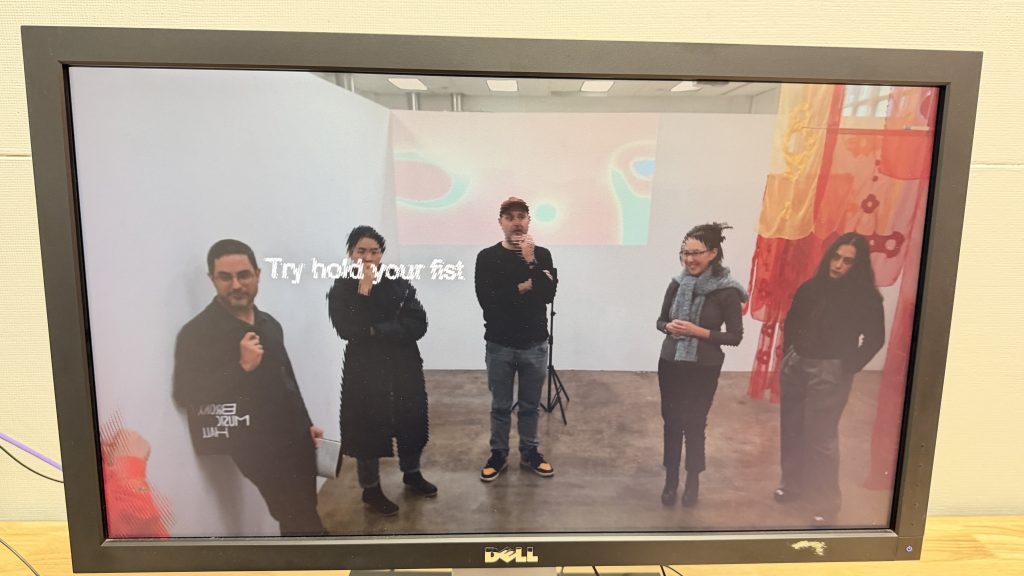

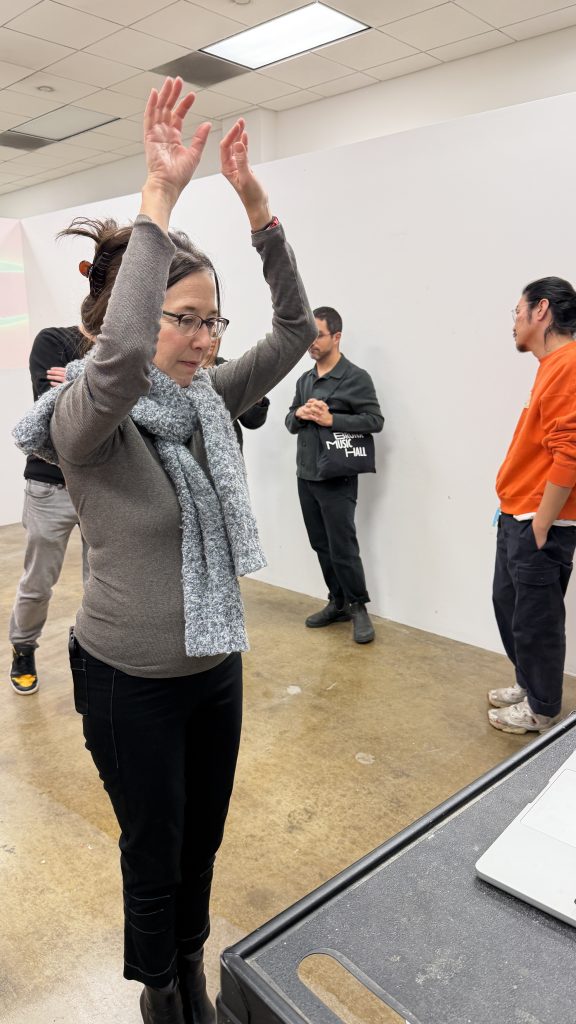

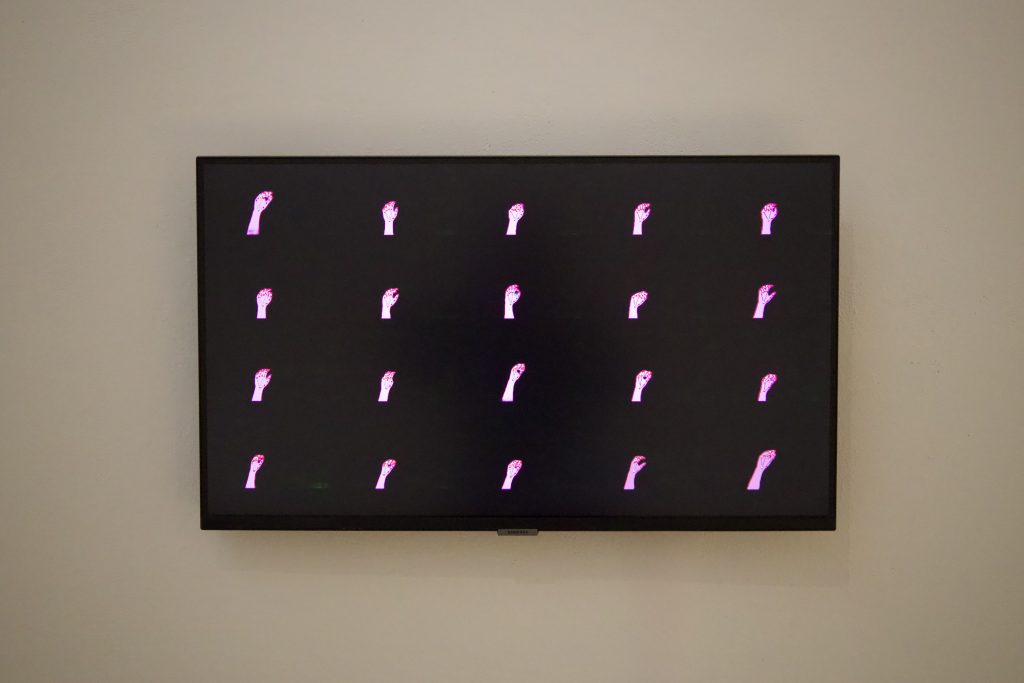

Chiyu Zheng

GESTIC

Material: Media Installation, TouchDesigner

Gestic translates everyday human gestures into live visual responses. Movement becomes a quiet language shaped by habit, culture, and presence.

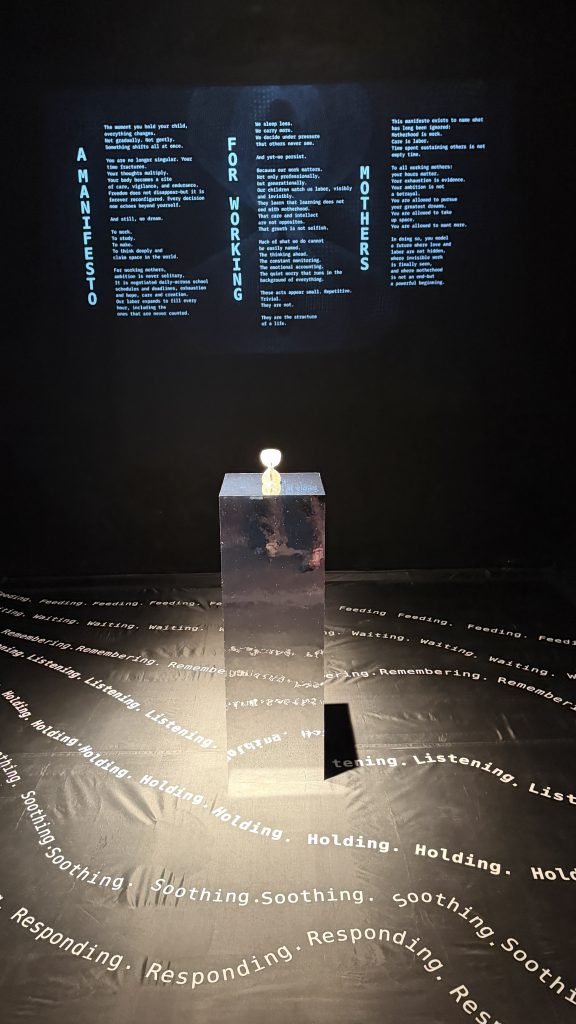

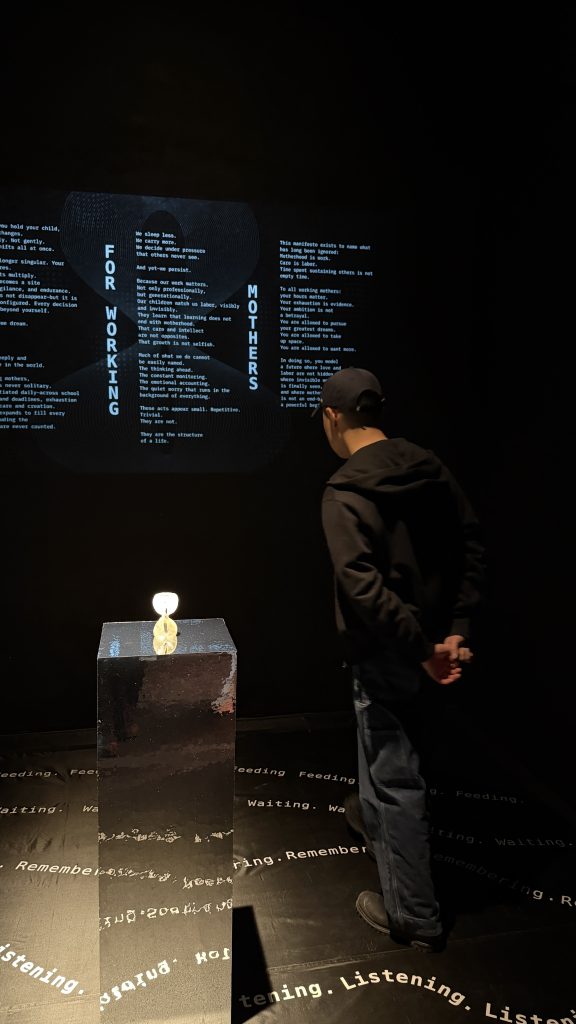

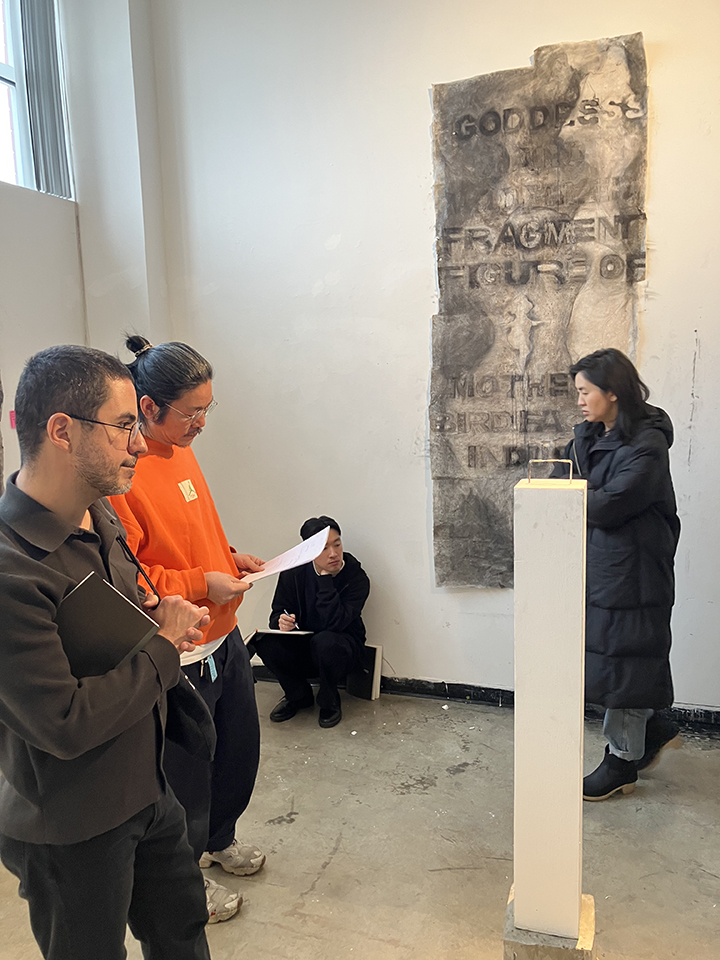

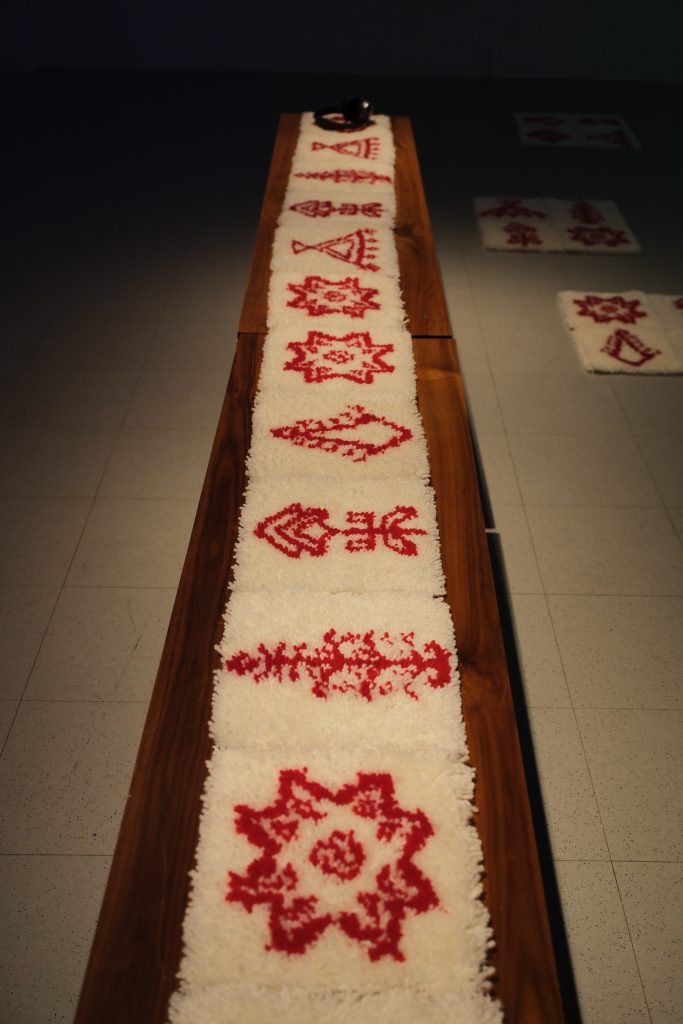

Mahsa Masoumi

SABR

Material: Video with audio, latch-hook weaving

Sabr means patience. The work unfolds the traditional Persian story of Zaal and Simorgh through image, sound, pattern, and repetition, inviting viewers to linger with care, endurance, and time.

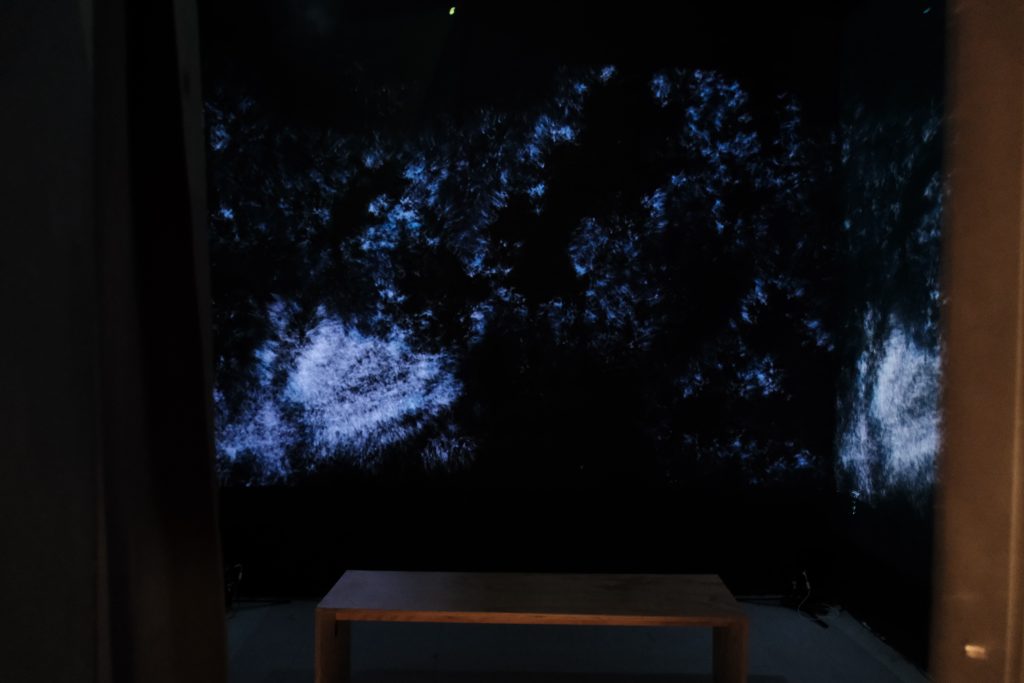

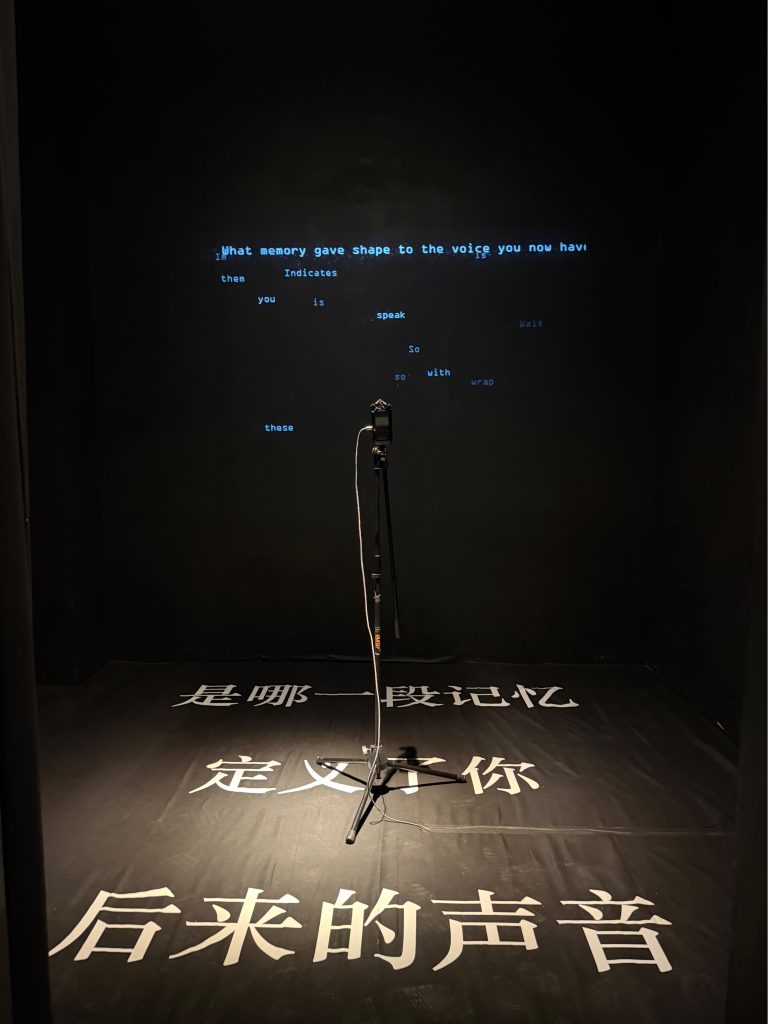

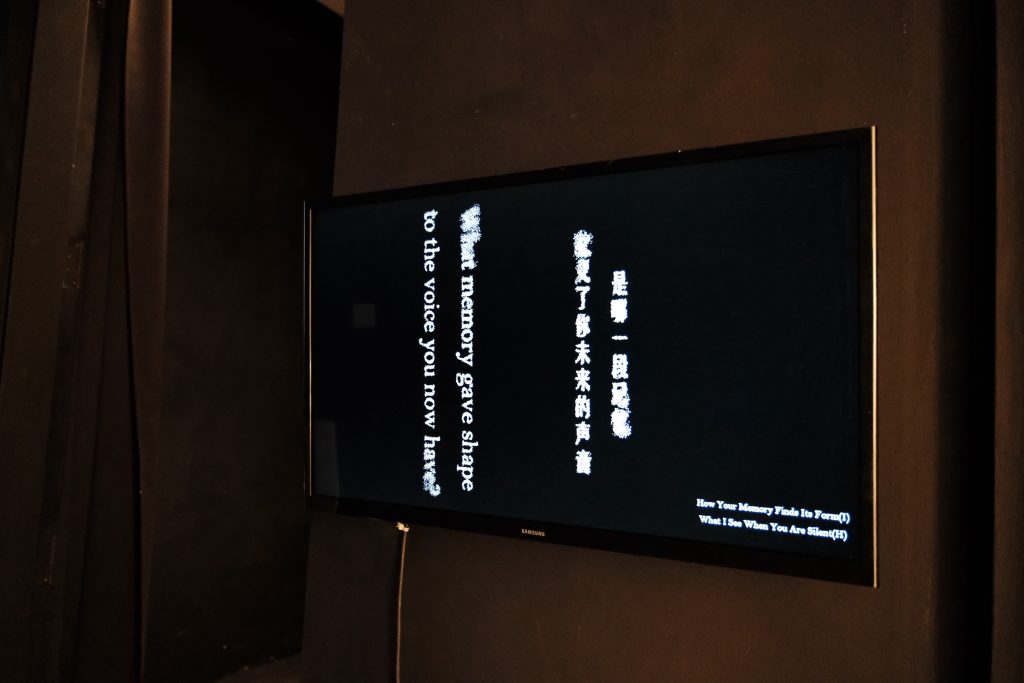

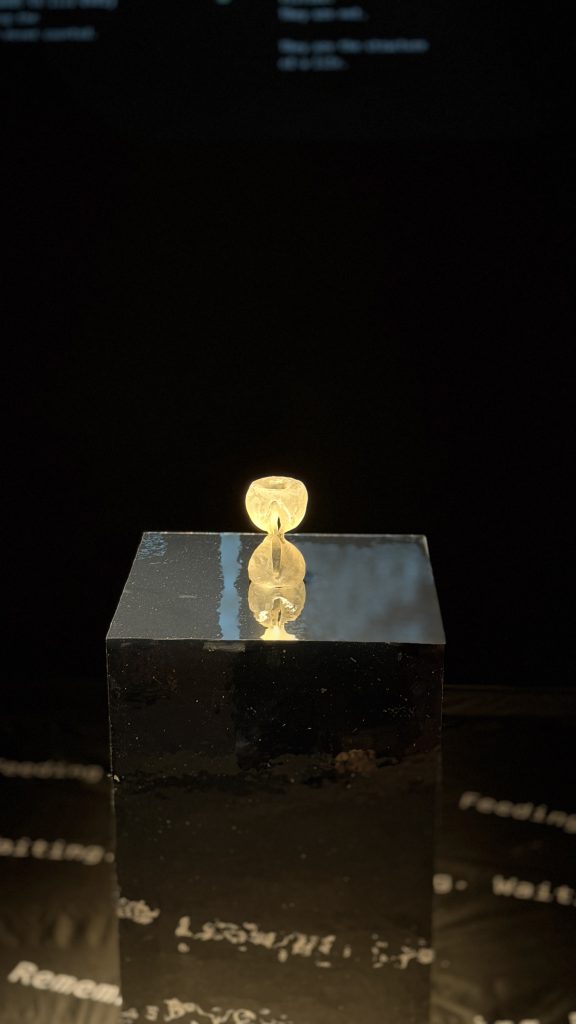

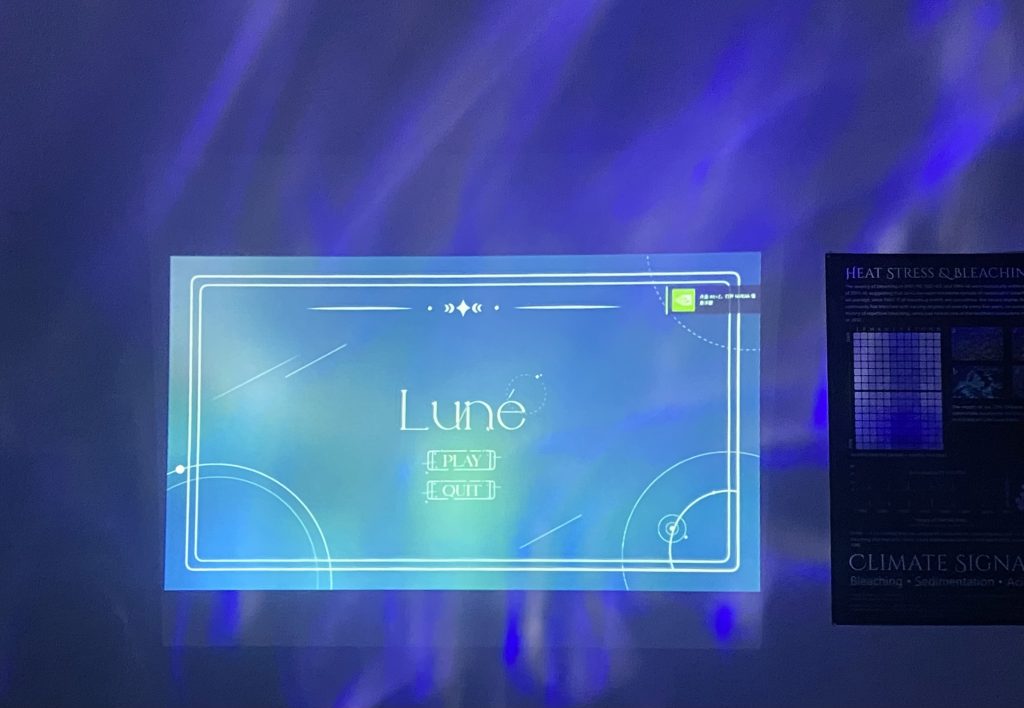

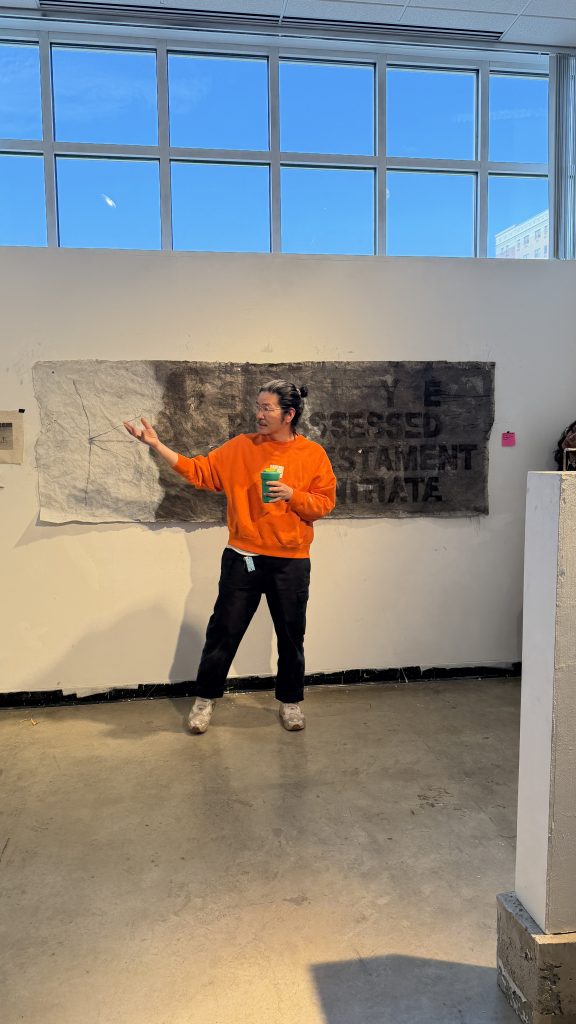

Yuxuan Hu

What I See When You Are Silent, and How Your Memory Finds Its Form

material: Installation, TouchDesigner, Python

This project responds to sound by generating images that appear, linger, and fade. The work reflects on memory as something that remains, even after the digital form disappears.